VOTER REGISTRATION ACROSS THE UNITED STATES

Elections are state-by-state contests. They include general elections for president and statewide offices (e.g., governor and U.S. senator), and they are often organized and paid for by the states. Because political cultures vary from state to state, the process of voter registration similarly varies. For example, suppose an 85-year-old retiree with an expired driver’s license wants to register to vote. He or she might be able to register quickly in California or Florida, but a current government ID might be required prior to registration in Texas or Indiana.

The varied registration and voting laws across the United States have long caused controversy. In the aftermath of the Civil War, southern states enacted literacy tests, grandfather clauses, and other requirements intended to disenfranchise black voters in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. Literacy tests were long and detailed exams on local and national politics, history, and more. They were often administered arbitrarily with more blacks required to take them than whites.Stephen Medvic. 2014. Campaigns and Elections: Players and Processes, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. Poll taxes required voters to pay a fee to vote. Grandfather clauses exempted individuals from taking literacy tests or paying poll taxes if they or their fathers or grandfathers had been permitted to vote prior to a certain point in time. While the Supreme Court determined that grandfather clauses were unconstitutional in 1915, states continued to use poll taxes and literacy tests to deter potential voters from registering.Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915). States also ignored instances of violence and intimidation against African Americans wanting to register or vote.Medvic, Campaigns and Elections.

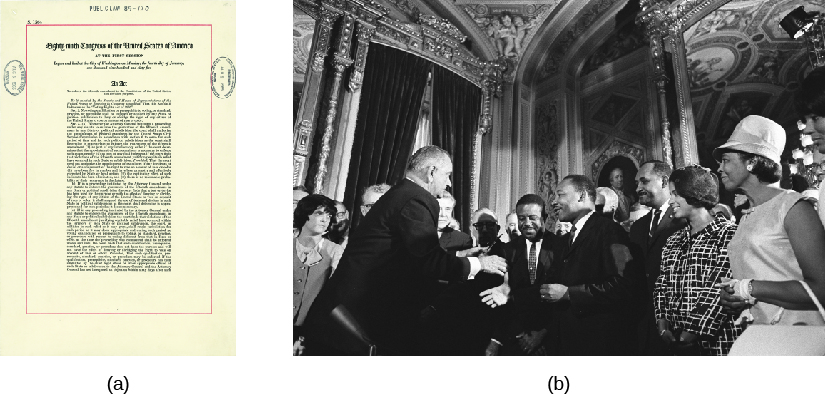

The ratification of the Twenty-Fourth Amendment in 1964 ended poll taxes, but the passage of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) in 1965 had a more profound effect (Figure). The act protected the rights of minority voters by prohibiting state laws that denied voting rights based on race. The VRA gave the attorney general of the United States authority to order federal examiners to areas with a history of discrimination. These examiners had the power to oversee and monitor voter registration and elections. States found to violate provisions of the VRA were required to get any changes in their election laws approved by the U.S. attorney general or by going through the court system. However, in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), the Supreme Court, in a 5–4 decision, threw out the standards and process of the VRA, effectively gutting the landmark legislation.Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. ___ (2013). This decision effectively pushed decision-making and discretion for election policy in VRA states to the state and local level. Several such states subsequently made changes to their voter ID laws and North Carolina changed its plans for how many polling places were available in certain areas. The extent to which such changes will violate equal protection is unknown in advance, but such changes often do not have a neutral effect.

The effects of the VRA were visible almost immediately. In Mississippi, only 6.7 percent of blacks were registered to vote in 1965; however, by the fall of 1967, nearly 60 percent were registered. Alabama experienced similar effects, with African American registration increasing from 19.3 percent to 51.6 percent. Voter turnout across these two states similarly increased. Mississippi went from 33.9 percent turnout to 53.2 percent, while Alabama increased from 35.9 percent to 52.7 percent between the 1964 and 1968 presidential elections.Bernard Grofman, Lisa Handley, and Richard G. Niemi. 1992. Minority Representation and the Quest for Voting Equality. New York: Cambridge University Press, 25.

Following the implementation of the VRA, many states have sought other methods of increasing voter registration. Several states make registering to vote relatively easy for citizens who have government documentation. Oregon has few requirements for registering and registers many of its voters automatically. North Dakota has no registration at all. In 2002, Arizona was the first state to offer online voter registration, which allowed citizens with a driver’s license to register to vote without any paper application or signature. The system matches the information on the application to information stored at the Department of Motor Vehicles, to ensure each citizen is registering to vote in the right precinct. Citizens without a driver’s license still need to file a paper application. More than eighteen states have moved to online registration or passed laws to begin doing so. The National Conference of State Legislatures estimates, however, that adopting an online voter registration system can initially cost a state between $250,000 and $750,000.“The Canvass,” April 2014, Issue 48, http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/states-and-election-reform-the-canvass-april-2014.aspx.

Other states have decided against online registration due to concerns about voter fraud and security. Legislators also argue that online registration makes it difficult to ensure that only citizens are registering and that they are registering in the correct precincts. As technology continues to update other areas of state recordkeeping, online registration may become easier and safer. In some areas, citizens have pressured the states and pushed the process along. A bill to move registration online in Florida stalled for over a year in the legislature, based on security concerns. With strong citizen support, however, it was passed and signed in 2015, despite the governor’s lingering concerns. In other states, such as Texas, both the government and citizens are concerned about identity fraud, so traditional paper registration is still preferred.